Final Considerations

Since this statuette and the fragment which accompanies it were found in the citadel of AK1 in the so-called "administrative quarter" (where both bullae and numerous cretulae have been found), one can only underline that among the nobles of AK1 there existed religious and cultural expression which were linked to Mesopotamian tradition. The fact that we ourselves found in the Gonur necropolis (T.n.560) a female statuette which was very similar; confirms that Mesopotamian culture was diffused throughout Margiana and, therefore, along the Road of the Oases, since in the context of this tradition only praying figures were places either in temples or burials, while images of divinities are completely unknown (cfr. P.AMIET: 2006). In the light of archaeological reports in our possession, we can only ask ourselves whether this statuette represents a beneficent and generic "companion" or whether, as at contemporary Shahdad (2400-1900 BC) it is actually a portrait of a deceased person. Towards 2300 in neighbouring Iran, Sargon of Akkad created the Empire of Agadé. As Pierre Amiet recalls, in this period a renewed cult of the Great Goddesses was widely diffused, perhaps allied to Akkadian imperialistic projects, reaching as fär as Margiana. This was an influence which lasted for about five centuries, from 2300 to 1800 BC: that is, until long after the end of Agadé (CFR: AMIE, ib.). Right from the start it is clear that a change, both cultural and religious, had taken place. The statuettes "with spread legs" disappeared and, as "companions" for the deceased or as spirit protectors we find pillar statuettes (group n.2), rather roughly made. This production continued until the end of the Margian settlements, reflecting a popular tradition. Also during this period, both in the Tedjen and in Margiana, the flat statuettes (group n.3) became dominant ad represent a style which is completely original and, as far as we can be sure, is typical of Turkmenistan alone. In the Margian context, initially, the figurines were still roughly made (type A), often incised with vegetable motifs which are associated with the cult of fertility.

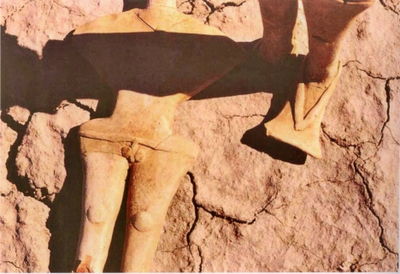

During the last mission (autumn 2006) numerous fragments belonging to this type of figurine were found inside several fireplaces attributed to phase1 in rooms n.202 and n.203. One fragment from room n.203 showed the abdominal area covered with small holes with the lower point bent forwards, reminiscent of the 'goddesses with spread legs ". Both for the context in which they have been found, together with their form, I believe that this group appeared in AK9 right at the beginning of the Bronze Age and continued until the Middle Bronze Age, embracing a time span between 2 700 and 2100 BC. From the following century, these figurines reach a mature form, flat and elegant (type B). On the head there appears a tiara embellished with a "V" (the chevron) which links it to the great goddesses of Susa, since these were also furnished with a tiara adorned with bull's horns.According to M.Gimbutas's interpretation (1990: 325 e pass.), this "V" which stands out on the tiara is the emblem of the Bird God, derived from the pubic triangle and also from the fact that the goddess has no mouth. This would reinforce her qualifying as a ctonic goddess, that is a Goddess of Death, one of the multiple aspects of the Great Goddes, Mother of All.

It should he remembered that these figurines were manufactured as part of a series and that they were displayed above all in the home or, during particular ceremonies, hung from the neck of devotees, while in only three certain cases out of about 4, 000 graves so far explored (between Gonur and Adji Kui) have we found this statuette type in grave contexts. This would not seem to support M.Gimbutas's theory, just as the "V"; the chevron, does not refer to the pubic area of a Bird God, but rather to the bull's horns and its alternative symbol, the crescent moon.

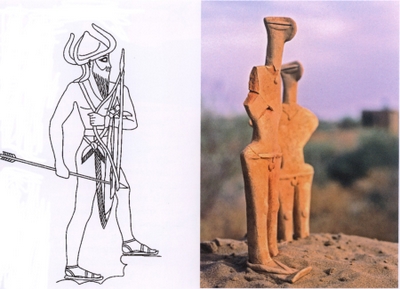

Virtually contemporary with the appearance of the flat statuettes of type 3B appear a few lanceolate male figures (type 3D) which certainly represent a hero, a genie or a minor god, which is evident from astral symbols incised on the shoulders and which present two holes for hanging. These examples were often found in association with female figurines of type 3B in deposits in AK9, dated to 2200-1940 BC: that is, covering the whole span of time during which Akkadian cultural influence was felt. As Pierre Amiet has observed, in the iconography offered by cylindrical seals of this period, minor male deities often appear, linked to war or the hunt, which move within the pantheon "governed" by the Great Goddess. Our statuettes are therefore perfectly consistent with the absence of a diadem, lance point schematisation, reduced dimensions when compared to female divinities. A further curiosity (but perhaps not by chance) is the fact that they once again, almost literally, show the lower part of the female statuettes, as if they wished to recall that these divine personages were subordinates of goddesses. Almost contemporaneously to the group 3B statuettes, images of more complete female divinities of greater dimensions (type C) appeared, which depart from the canons of the flat goddesses and which clearly show a process of rapprochement of the female to the male canons, which matured towards 2100 with the appearance of the group E and the stupendous standing figures with distinct legs (type F). Now a god overtakes the Great Goddess both in stature, with the addition of primitive schematic legs (the "lance') and once again exhibiting his "divine" nudity, underscored by the use of shoes. These two symbolic elements confer great dignity and we find them once more in Elamite contexts.

In fact, it seems that this "change of guard" could be linked to the ideological change happened during the Naram-Sin Reign (2254-2218 BC); he tended to give the king an unprecedented charisma, drawing him near the divinity, so much that, before the name of the king, sometimes he put the divine attribute, ilum. To the point, it does not seem casual that in the famous "Stele of Naram-Sin" (ca 2250 BC), considered an important stage in the process of deification of the Akkadic king, he is represented with the shoes and the belt. By now, the God of the Skies, with his astral symbols, imposes himself on the Goddess of the Earth. The roles are now reversed.

The final phase of this journey, which concludes with the crisis of the whole system which has been proven by the advance of the nomads (or with the return of nomadism, as Amiet suggests), another type of figurine from the East makes its appearance, this time in stone. These are the celebrated statuettes of Bactrian tradition. As we have seen, we know very little about them as only three have been found in context: one at Quetta, one at Gonur (grave n.1799) and one at Adji Kui (grave n.018). It is therefore difficult to interpret them as images of the Great Goddess, both because they appear in an era in which male supremacy had already been established in the religious field, and also because up to now they have been found in a funerary context, which would lead one to suppose that their role was either that of "companion" to or a portrait of the deceased. This last hypothesis would seem to find confirmation both from the variety of clothing (from the hairstyle and the head-coverings in particular) and from the fact that, since they were modelled separately, the heads could have been made as wanted or by commission. Because of this, quite rightly, we prefer today to dejine them simply as "Ladies" or "Princesses" of Bactria, awaiting further discoveries in context.In Margiana the epic of the Great Goddess faded at the end of the III millennium BC, when the "male" states which reverberate in the myth of Etana was established. The Great Goddesses first of all became supporters of the males, then companions, and were finally subjected to that God of the Sky who would govern a new pantheon, delegating to the goddesses specific but always subordinate functions.

(ibid., p. 186-191)

Source: Rossi Osmida, G.: Adji Kui Oasis. Vol.I: The Citadel of the Figurines.Venice: Il Punto Edizioni 2007.