The Synagogues of Herat, Afghanistan

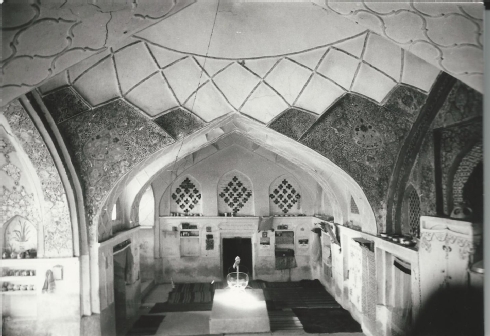

Herat—like other Islamic cities such as Aleppo, Cairo, Fez, Isfahan, Jeddah, and Sana’a—is the embodiment of a living city with traditional Islamic influences. Its architectural design was, for the most part, predetermined by Herat’s geometric urban concept and system, which was designed to meet the Islamic requirement to face toward Mecca (qibla). The city’s historic and vernacular architecture, and its exceptional surviving architectural heritage of both Muslim and non-Muslim origins, illustrate the complex processes of a global cultural transition. Targeting the “internationalist dimensions” of two world religions (Islam and Judaism) by using reverse theoretical approaches and methods, this investigation of Herat’s four synagogues in an urban context illustrates the complex processes and design elements through which like-minded believers could be identified through their shared beliefs (“communities of opinion”).84 It also reveals the role of religion as the driving force reflecting the unity and diversity of the Muslim and Jewish identities and the practices of the Jewish Diaspora living in the Muslim world.

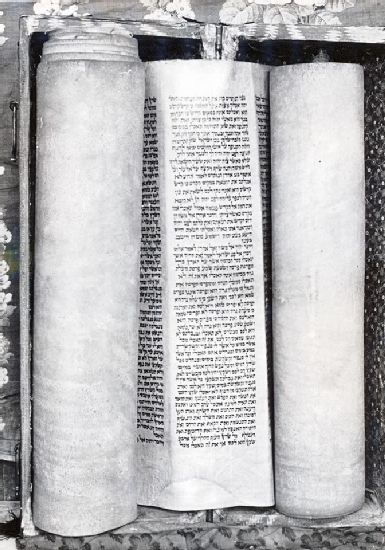

Documentary evidence analyzed for this project has enabled a partial reconstruction of the original architectural structure of Herat’s four synagogues. Their design and construction followed styles that combined both local and universal elements—while also deeply influenced by variations in Jewish tradition. The history of these four remarkable buildings—beginning with their construction from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries—to the time when they closed in the 1950s, Herat being abandoned completely by Jews in 1978, and then bombed by the Soviets in the 1980s—is one of transition, cultural adaption, and reciprocal influences between Herat’s Jewish minority and the majority Muslim population. This reciprocity is demonstrated in the intricacies of Herat’s Jewish life on the macro and micro scale—from Herat City to the detailed interiors of the four synagogues.

In examining sacred realities in an urban context, religious cultural exchanges, and the transnational historical experience of different faith communities in an increasingly globalized and politicized world, the present study suggests that we need to rethink our current understanding of the concepts of “religion,” “religious identity,” and “freedom of religion” in the modern world. Indeed, it is hoped that this chapter will contribute to a critical understanding of both ancient and contemporary globalized religious dynamics. It suggests the need to critically reflect on intercultural influences (political, social, religious) in light of religious multiculturalism and the transnational historical experience of different faith communities.

Finally, this research may also spark an interest in determining how intercultural and international negotiations on (religious) self-definition can both reduce conflicts and facilitate the peaceful coexistence of different religious communities. This area of inquiry is becoming visibly important, based on the growing and increasingly unscrupulous influence of religious splinter groups that attempt to promote their own political interests while disregarding the long-held traditional beliefs that have hitherto bound together and governed communities of faith.

Copyright Ulrike-Christiane Lintz